Preface - It's Your Funeral

Dear friends (those who are left),

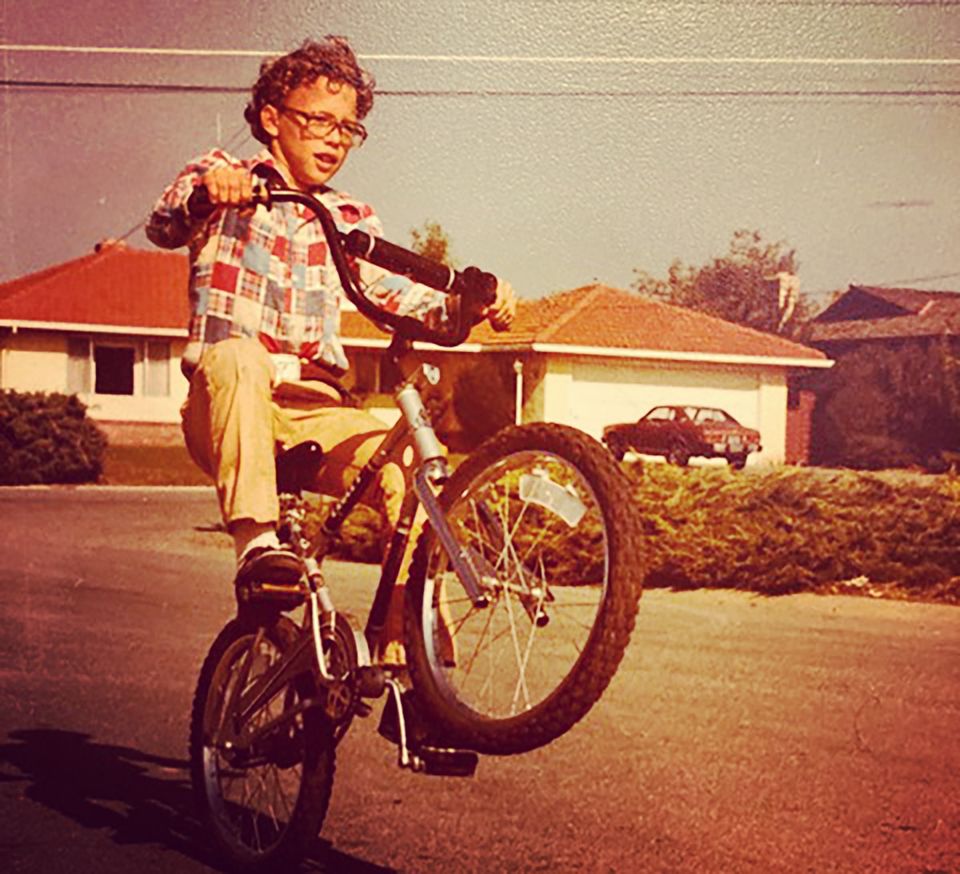

By now you probably know that I am writing the Story of my life. While I’ve spent years contemplating this project, I suspect that many in my audience have been caught off guard by the form, the content, and especially by the candor. You thought you were getting a quaint little tour of my 1970’s childhood, when BAM! – suddenly, you’re watching me in fifth-grade, discovering Playboy and Penthouse in the aftermath of my parents’ divorce. Ouch.

It is hard to read.

It is hard to write.

It was hard to live, too.

But this is what happened.

Since I’ve started, and this is the only Story I’ve been given, I feel obliged to try and tell it, as well as I am able, for at least a little longer. And since I’ve let you in on it early (as friends), I think it might be helpful to let you know more (as readers) about why I am writing (motive), and to what end (purpose and means).

First, I am aware that many will find my telling difficult. This is hardly surprising. I have been writing for years, but this is the first time I’ve attempted something this long, in the form of a story (memoir). The subject matter is challenging. Plus, I am seeking to write with a level of honest, transparency and candor that some will appreciate, but others may find discomfiting. None of this comes easy. I do not lightly set my hand to this plough.

But I take my duty as Storyteller seriously, and I see this as my fundamental task: How do I do justice to the Story?

Will I succeed? Who knows! But this is what I am attempting. (As Dad always used to say, “You don’t have to be crazy, but it helps…”) Your patience, prayers and charity are greatly appreciated.

Second, I anticipate that some (particularly family members) might find these recollections painful. They are painful for me, too. But just because things are painful, doesn’t mean they shouldn’t be discussed.

Over time, I have come to think that the carnage of our past – left unprocessed, unconsidered, undealt-with – will inevitably shape, condition, and contribute to the carnage in our present. More precisely, as I have spent years reflecting on my own personal struggles as an adult (particularly as a husband and a pastor), I’ve discovered deep and enduring connections to the events – good, bad, and ugly – in my childhood (the first six chapters of my story).

So everything I am writing is in there for a reason. Even the cusswords, and the parts that make you squirm.

All of these things will bear fruit downstream. Hopefully.

As such, these stories from the past shed light on who I am, on what I have become, on who I am becoming. That interests me; I feel it worth discussing. I think we humans could do with more real, honest, concrete conversations about our pain and brokenness – where it comes from, what to do about it. Naturally, I can’t force anyone else to talk about their trauma; I can, however, choose to talk about mine. I think it is worth any potential discomfort.

Third, this is my story. It’s not about my parents, or Grandpa Don, or even my wife Marilyn. Sure, they’re all in there (or will be) – but they’re making cameo appearances, to put flesh and bone on what could easily become stick-figure names, places, events. I include them to chronicle what really happened. And I take it as a matter of highest importance to represent them well – by that, I mean, as they really were, not merely as they (or we) wished them to be.

Fourth, memories are fickle. Remember my recollections about Chili Cheese Fritos in Chapter 6? It didn’t happen. Or at least, not as I remember it. Frito Lay didn’t introduce that particular flavor until the mid-‘80s. But there it is, firmly ensconced in my memory from 1979. Whatever chips I ate on the beach that sun-soaked afternoon… they weren’t Chili Cheese Fritos.

Even now, I find this unsettling; for the past forty years, this particular memory – Fritos on a beach – has functioned as a sort of emotional bedrock to my sense of self. I rarely eat chips, yet once or twice a year, usually on a road trip, I get this intense craving for Chili Cheese Fritos. And when I eat them, all these memories come flooding back, reassuring me of who I am and where I came from: This thing happened. You can be absolutely certain of that!

It's odd what our memories tell us about ourselves. And in this particular case, my memory cannot be entirely accurate.

Why mention this?

Even though our memories are not infallible, we usually we act as if they are. Recognizing this, I tend to tread lightly and hold loosely the further back we go. I try not to be dogmatic when I’m not sure. I try to leave open the possibility that I am remembering incorrectly. If you see places where you think things happened differently, I’d love to chat about it so I can do my best to get it right. I'm after truth here. And what that truth means for me.

Fifth, let’s talk about the structure of my narrative. In 1947, J.R.R. Tolkien (author of The Hobbit and The Lord of The Rings) wrote a short essay entitled On Fairy Stories. In this article, Tolkien pondered what made fairy-tales so emotionally satisfying; and he posited that the best fairy-tales all utilize a curious literary structure he called a eucatastrophe (“a good disaster”).

Tolkien coined this term himself, because he could find no suitable English word for the concept he was trying to describe. As an Oxford professor of English language and literature, and a contributing author for the Oxford English Dictionary, Tolkien had a pretty good grasp of English – when he couldn't find a suitable word, it was because a suitable word didn't exist. So in the case, he created one. When Tolkien landed on the word eucatastrophe, he was not simply talking about "happy endings". Rather, he was observing that often in the best myths and fairy-stories, there comes a moment of great disaster or catastrophe that is (unexpectedly) accompanied by a sudden joyous “turn”:

[It is] a sudden and miraculous grace: never to be counted on to recur. It does not deny the existence of dyscatastrophe, of sorrow and failure: the possibility of these is necessary to the joy of deliverance; it denies (in the face of much evidence, if you will) universal final defeat and insofar is evangelium, giving a fleeting glimpse of Joy, Joy beyond the walls of the world, poignant as grief.

So, a eucatastrophe is some sudden and unlooked-for good, achieved not just in spite of great disaster, but rather through it, and what it brings with it is nothing less than heart wrenching Joy. Example: when Sauron is (against all odds) overthrown through Gollum’s betrayal, Frodo is permanently wounded (physically, emotionally, socially), ultimately losing his ability to enjoy the very Shire he helped save. Frodo sails away over the sea. His best friend Samwise returns home alone. The world is saved through their friendship. But it costs them everything.

That’s eucatastrophe.

As a writer, Tolkien understood that his reader’s emotional response would not be anger or dislike (that was a terrible ending!) but rather, one of hope and joy (that was amazing!). And, he noted: the more costly the sacrifice, the greater the joy.

Again, why mention this?

I have found it helpful to think of my own narrative through the lens of eucatastrophe. (I told you Tolkien left a major mark on me.) Specifically, I see my own Story in terms of three great disasters:

- the first being my parents’ divorce and my subsequent year in California (chapters 1-6);

- the second, my own up-to-the-edge dalliance with infidelity (in my thirties, while at seminary);

- the third, a gut-wrenching betrayal from church leaders I counted as friends, in the congregation I had just spent seven years building (a decade later, in my forties).

Each of these disasters have yielded surprising silver linings. They have enhanced my understanding of my brokenness, and of my faith. They have profoundly influenced how I think people change, and what God really wants of us. But in order to describe the good that has come through these disasters, it is also necessary to talk about the darkness they brought – where it comes from; what transformed it; what didn’t help.

Sixth, I believe the true test of any theology (e.g. the convictions we have about God) lies in how well it describes reality and answers the brokenness in this world.

In other words, what difference does our Truth make?

Does it provide a map of the real world – the one we find ourselves in, where people do terrible things to one another (and then live with the consequences forever)? Is that map accurate enough that we can navigate by it – over rough roads, stormy seas, through pain and disaster? Where do our truth-maps take us? What hope do they offer for change? Do they carry any real transformative power for healing and change?

This is what I really want to write about.

But I am not blind to where we are, culturally.

I have a hunch that Christianity in America is at a crossroads. To my ears, many who still identify as followers of Christ (unfortunately) often sound more American than Christian (in any first-century sort of way); I have no idea whether these folks will have any interest in what I am writing about. I am okay with that.

I also know many who have moved on from Christian faith (or never seriously considered it) because the only versions they have encountered felt shallow, superficial, irrelevant; it did not answer their realities in any sort of compelling fashion. I am very interested in writing for these sorts of folks – the poor, broken, marginalized, hurting. (Boy, can I relate.) But also for the curious, questioning, skeptical, wondering-if-there’s-another-way-out-there sort of folks. (Because I think there is.)

The only way I know how to talk with salt-of-the-earth folks like this is by being salt-of-the-earth myself. And that starts with me being relentlessly honest about my own Story (good, bad, and ugly).

So far, I’ve written and shared about 16,000 words (chapters 1-6); to me, the next two disasters are where things really get interesting. But like I said above, writing is hard. Don’t be surprised if my Story goes underground for a while as I work on it – it could take a couple of years to get to where I’m going. I will keep you posted.

One last thing.

If you’ve read what I’ve written thus far, you know I write a lot about my pipe-smoking, scotch-drinking, salty-as-a-sailor grandfather (inadvertently) introducing me to pornography. (What grandparent wants that on their resume?)

It would be easy to write off someone like O.D. Cryder as a dirty old man… but I find that reading superficial. Scratch a little deeper, and a much more complex person emerges – yes, he could be gruff and hold grudges; but he was also warm, compassionate and caring. He was always kind to me.

So how would O.D. feel about his preacher-ass grandson sharing all this stuff? In terms of reputation, he probably has the most to lose. (So far. Just wait till you get the dirt on me.) Ironically, however, he might not be bothered as much as you’d expect. Sure, he’d feel some chagrin (who wouldn’t). But Grandpa Don didn’t give a rat’s ass what other people thought about him, and he didn’t feel the need to tell other people how to live, either.

“Hell, Chris…” I can hear him say (pipe clamped firmly between his teeth). “Do whatever you want… It’s your funeral.”

I take this as an under-appreciated aspect of his spiritual maturity. After all, Jesus says we can expect to answer for every careless word; the Apostle Paul tells us to confess our sins to one another. It seems that both those things require attending to our past – mining our stories for motive and meaning, then owning our part in the narrative arch (without being owned by it).

So maybe Grandpa Don was on to something. I know the more I remember him, the more I admire (and miss) him.

This is my conclusion: the more I press into my recollections, the more I try to write about my past in a way that honors what really happened (good, bad, and ugly) – the more I find myself appreciating the story that has been written for me, along with the people who have inhabited it.

So perhaps this is really a love letter to my family, rather than an expose of it. And maybe writing about the pain can actually be an act of faith that helps us find our way home, through the pain.

Is my hope wise or foolhardy? There’s only one way to find out. Ultimately, you alone can decide if it was worth it. But in order for you to read it, first I’ve got to write it. So here goes nothing…

Christian Cryder

April 21, 2023

Member discussion