4 - The Crash (Part 2)

As a pilot, my dad has zero interest in skydiving or parachutes: “Why on earth would you ever jump out of a perfectly good plane?”

If you take anything with wings – snuff out the engines, shoot it full of holes, light it on fire, send it spiraling towards the ground – he’ll try to land it, rather than jump out of it, any day of the week. Did that come from his Marine Corps training? Or would he rather just bet on himself than trust a backpack full of silk? Either way, any plane still in the air is “perfectly good” for him.

“Besides,” he gruffs. “Falling’s easy. It’s the landing that’s hard.”

I’m not sure I agree.

I think that often in the fall, right before the crash, we sometimes experience a strange, almost mystical flash of precognition – we look into the future and we see what’s coming.

It happened to me in Sun Valley, that summer afternoon in 1979.

We are landing Grandpa Don’s newly purchased red 1948 Stinson. Dad found it gathering dust in the barn of an old friend of Irv’s out in Fallon somewhere. (What’s with all these ranchers having planes?) Oris Don bought it, Dad and I are delivering it, and here we are, almost to the finish line – wheels on the ground, racing up the runway... but still way-too-fast-to-stop.

Which, as it turns out, is a bad place for something to go wrong in an airplane.

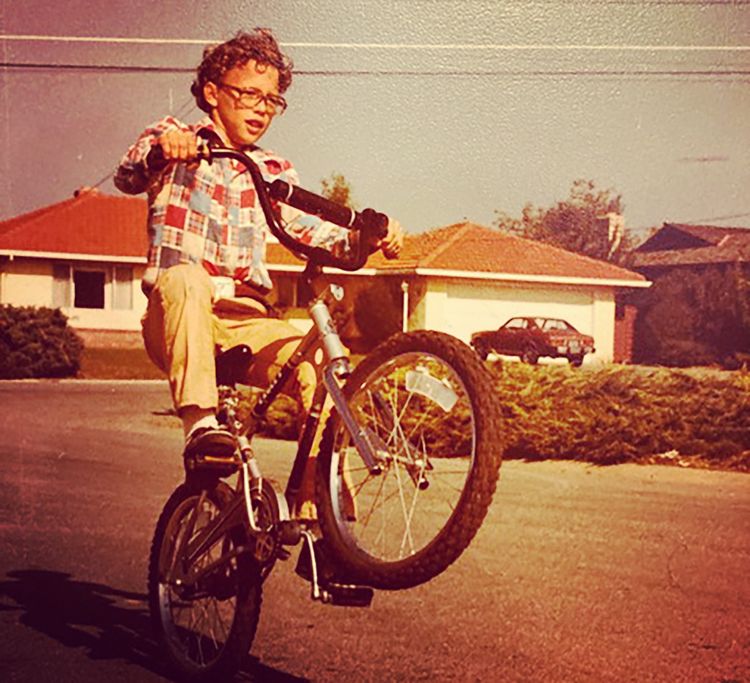

I have just finished fourth grade. My imagination is on fire with Star Wars (released last summer). I am pining for Adventure. Flying cross country in a small plane with your helicopter-pilot-Dad seems like a pretty good start.

I am already getting the hang of this flying thing (I only barfed a couple of times in the last two days). I could get used to this…

As we are landing, I remember looking out the window, taking in the scenery, while the wingtip dips, lower and lower, till it is almost kissing the ground.

Suddenly, something clicks: Wait a second! We’re going to…

CRASH!

We are head over heels on the tarmac. The world spins, turning upside down as steel grinds against asphalt and the cockpit explodes.

(Ok, I’m exaggerating, but only slightly. Dad had several boxes of magazines in the back seat; the plane cartwheels, and I am left dangling by my seatbelt, old issues of Fur Fish & Game raining down upon me. My glasses have come off; I can’t see a thing. It felt like an explosion.)

Meanwhile, Dad is frantically trying to get me unbuckled and out of the wreck before something catches fire or blows up. All I can do is yell about my glasses. (I wonder how many crashes he saw back in Vietnam? What is it like to crash a plane with your kid in it? Was everything in him screaming, Get out! Get out! Get out! Nevertheless, he crawls back in and finds my glasses.)

What interests me most about this memory is that instant of recognition, of precognition - right before it happens.

- It happens in traffic, when car tires screech and you suddenly realize: I’m about to get hit…

- It happens with bosses, when they ask you into their office and you suddenly know: you’re being let go…

- It happens with lovers, when you suddenly recognize: no matter who says what next, this relationship is over…

- It happens in the mountains, when that boulder shifts or your foot slips and you suddenly see just how easily: you could go over that edge…

What we find so disconcerting is the suddenness of knowing truly.

Not all these moments end in disaster (a literal crash). But they do feel like falling. And sometimes we see the future. And that vision almost always induces vertigo: the bottom drops out, we see the ground rising up, and we know the landing is going to hurt.

In that instant of knowing, I think the fall is very hard indeed.

Looking back, that plane crash was a portent, the first rumble of thunder which warns you the real storm is coming.

But two other things happened about that same time, which would later prove to just as significant in the plotline of my story.

First, I discovered Tolkien.

For me, summer always began on my birthday. That falls at the end May, so school would be almost out, with vacation right around the corner. In the years when it would land on Memorial Day Weekend, we’d celebrate (both my birthday and the three-day weekend) by camping in the mountains.

But May 29, 1979 landed on a Thursday. I turned 10 at our house in Lockwood. And Grandma Balster gave me a brand-new boxed set of The Hobbit & The Lord of The Rings.

(This was the 1975 Ballantine Books edition: cheap mass market paperbacks, bundled in a shiny gold cardboard slipcase. There were elvish designs printed on the outside, with Tolkien’s own artwork on the book covers. I was enamored, smitten. It was the first book I signed inside the front cover: Christian Cryder, 1979.

It was the most grown-up thing I had ever been gifted. Over the next twenty years, I would read it over twenty times. But it was particularly important in the aftermath of The Crash, where it functioned as a lifeline. Later, it would send me seeking in a new direction. But that’s getting ahead of the story…)

To this day, it remains one of the most important gifts I have ever received.

Still, what was she thinking?

I was 10 years old.

I charged through The Hobbit in less than a week, but I was a voracious reader and Tolkien wrote that tale for kids. The Lord of The Rings proper is more serious business, even for adults.

His three-volume trilogy is dense, dark, daunting. More significantly, his writing deliberately and unapologetically operates in the domain of all great mythic sagas: it paints a tragically realistic picture of human loss and suffering; but it also aims to answer why, in the face of overwhelming odds, our hearts are noblest when we hope, struggle, and sacrifice for what is good, beautiful, and right (even when it is fading away right in front of us, and costs us dearly).

He calls this 'fighting the long defeat.'

Tolkien said he wanted to see if he could succeed at telling a good, long, tale. (His readers’ common complaint: it was too short.) I found the vastness of Middle Earth intoxicating - names, places, backstory, and elves! I was in over way my head, and loved it.

I waded in and just kept going; slowly but surely, I learned to swim.

It took me most of June to finish. To this day, I have still never experienced anything like it. But the first time was magic.

Now Dad was on the road all week, and Mom was learning to play tennis. That meant we spent a lot of time at Pioneer Park. And that's where I first felt the shadow, or maybe just an inkling... something wasn't right. But maybe that’s because I was busy reading about Frodo and Gandalf and Black Riders infiltrating the Shire.

After her lessons, Mom’s tennis instructor would sometimes buy ice cream for us kids. I remember: eating felt like betrayal.

(What were supposed to do, anyway? We were kids – 10, 7, 5, and 2. You go where you are taken. You do what you are told. You eat the ice cream when the tennis instructor buys it for you. You don’t ask questions. You don’t think thoughts. Even at 10, there are already certain ideas you don’t even want to consider. Can you feel that sense of falling? Or am I just projecting?)

I never mentioned it to Dad.

Each day, all June, we’d be back at the park all over again. Mom would go work on her serves and we kids would be on our own for a few hours.

That's when I would escape.

I would lay there on a patchwork quilt in the shade underneath those big old cottonwoods while the sun dapples patterns on the grass, and I would find myself in another world – a world of heroes and dragons and battles and kings and little folks finding their way through all of that. I had discovered other worlds in books before, but none like this, and none like this since.

Middle Earth was the first world that felt as real as ours.

I desperately wanted it to be true.

Second, I discovered Mountains.

Of course, I knew what "the mountains" were already. The Beartooths were just sixty miles southwest of Billings. We went there a lot.

I caught my first trout in West Rosebud when I was 6. I remember camping in the back of Dad’s truck up on Hellroaring Plateau a few years later – that was back before it was wilderness area; if you had four-wheel drive, and knew what you were doing, you get all the way up on top of the world back then – or at least to the base of Mount Rearguard.

Below the peak, there’s a shallow valley about three miles long, running west to east, with twelve or thirteen lakes. It’s a steep hike down into the valley, but the bottom was all flat and easy. So it was a perfect place for kids.

All those lakes are all loaded with trout – brookies mostly. First stocked by miners over a hundred years ago, the fish in these lakes are now self-sustaining and fiercely determined, even if most of them are a bit on the runty side. They are almost always hungry.

I remember hiking there with Grandpa Balster. I was big enough to carry my own pole. And I was real serious about fish. We usually caught a mess of them.

Even back then, we were always fly fishermen. Not like in A River Runs Thru It, with actual fly rods. That would come later.

Fly-fishing is tough up here. First, you’re on the edge of tree line, with scrub pines right at your back. Second, it’s usually windy as hell up on top of the world. It’s hard to cast a fly rod in the wind with trees at your back.

So we used normal spin-casting rigs, with bright orange floats (“bobbers” were for bait fishermen) shaped like torpedoes. My dad had these old Shakespeare reels – even back then they were ancient – they had a closed metal face, but no push button on the back. To cast, you’d pinch the line with one finger, back-pedal the handle with your other hand; once it clicked you were ready to cast. If that sounds complicated... well, I had it down by 6. (Remember, I was serious about fish).

Those old reels would cast a mile. The floats gave you plenty of heft, plus the torpedo shape was aerodynamic. You'd tie on a piece of leader (“tippet”) to the bottom of the float, then you tie your fly onto the bottom of that.

"The secret weapon," Grandpa confided, "is a Grey Hackle Peacock". That single fly, retrieved through the water, will attract even the wily-est trout, unlocking his jaws like magic, inducing him to bite.

"If you have that fly, you will never go hungry in the Beartooths."

Which is pretty much true, until it isn’t. (Then you switch to another fly. Grandpa was full of wisdom like that.)

The point is, he knew all about the mountains.

So I knew all about mountains too. But I knew about them from roads, from the places you could drive to, or day hike. I knew them from the stories that Grandpa would tell.

But I wanted to get off the beaten path, to go where the big fish were.

I wanted Wilderness.

In the summer of 1979, Dad finally took me backpacking.

We left on a Friday night after work. As best as I can reconstruct, it was the first week in July. We drove to the Lake Fork trailhead, about fifteen miles southwest of Red Lodge, right off the base of the Cooke City highway. From there, we hiked the first few miles by moonlight in the dark, then pitched our tent beside Broadwater Lake (basically just a wide spot in the stream).

I carried my own pack, with a sleeping bag, canteen, spare clothes, and my fishing gear. All told, it weighed just over 20 pounds. Sam, my dad’s loyal Chesapeake Bay Retriever, accompanied us.

We would eventually hike our way ten-plus miles into the wilderness.

Along the way we forded icy streams, trekked across boulder fields, bushwhacked through downed timber, and eventually pitched camp again on the shores of Black Canyon, a lake that is fed by Grasshopper Glacier.

(No kidding: hundreds of thousands of years ago, swarms of locusts were entombed in ice when they tried to fly across a mountain pass and got caught in a snow storm. Montana is like that. It eats your lunch. Now they are fish food. No wonder those trout get so big.)

Mountain goats walked through our camp that night; massive rocks crashed down the surrounding cliffs by day. We were the only ones there. We were in the wild. It was almost mythical. That trip lit a fire in me that is difficult to explain. It endures to this day.

I remember standing on the north shore of the lake, high on a rocky outcrop. When the sun is just right, you can look down into the water and actually see the trout swimming.

And I remember Dad, looking way out, farther than I could ever dream of casting, to point out a massive cutthroat, ambling through the chop right below the surface.

“See that fish?” he said. “I’m going to catch him…”

Then Dad hauled back on his rod, and he let loose a mighty cast: his Shakespeare reel sang, that orange float flew, his fly – it was a black and yellow Bitchcreek… (I wasn’t allowed to cuss back then, but it was fair game if it was in the fly name, and what trout could not be smitten by a fly named ‘Bitchcreek’).

And that fly soared a million miles through the clear blue sky till it landed smack dab perfect about four feet in front of that big fish.

Dad gave one slow pull… and that fly twitched, and that big ‘ol trout rolled on his side, and his big 'ol mouth opened up wide enough to swallow a whale. Then it snapped shut, and Dad set the hook.

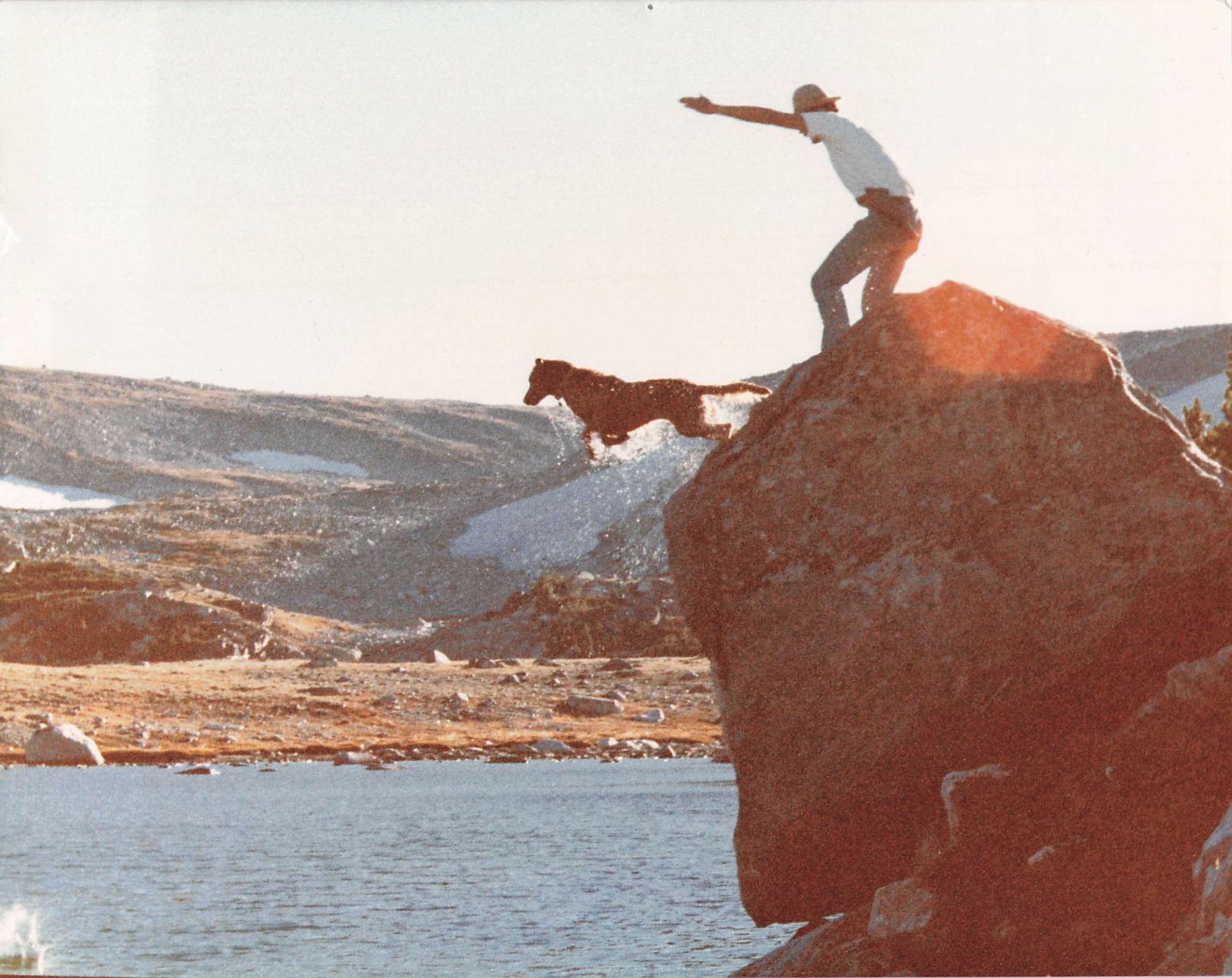

That fish exploded out of the water. But Dad landed him, fair and square. He was four pounds at least. I still have that photo of Dad leaning back beside the lake.

It was one of the last times I saw him happy.

We had planned on three full days in the backcountry, but Dad had this strange, nagging feeling that something wasn’t right… so we broke camp early. Back down in the main canyon, we took a quick detour up the Lake Fork, where he snapped my favorite photo of all time – me and Sam, on the shores of Keyser Brown.

And then we headed home.

It was my first backpacking trip, and I will never forget it. We caught fish, found an arrow, drank straight from mountain streams. I was hooked and smitten by an overwhelming love for the mountains.

Which is a good thing, since life often feels like wilderness.

The last two memories haunt me.

The first – I remember Mom, on the Last Day, standing on the porch in Lockwood. Less than two months after hearing about their divorce, she is saying goodbye to me and Dad, while her tennis instructor boyfriend is out in the street, waiting behind the wheel of our red Datsun station wagon, my sister and brothers in the back.

Mom hugs me, says she’ll write. (How are you supposed to respond to that when your world is ending?)

Then she turns to Dad, gives him a quick kiss on the cheek...

“I think I’m making a mistake…” she says.

And with those final, fateful words, she gets in the car and is gone.

And my world falls apart. (Again. And again. And again...)

(To this day I wonder: Did she really say that? Or has my mind just manufactured this moment to fill some void? I asked Dad about it once. He was emphatic, “She never said that – she never once apologized!” But I don’t hear her apologizing. I hear recognition, maybe – that moment of seeing right before the crash. Where did this memory come from, if I didn't actually hear it? I have no answers. Again, I lack the courage to ask. Sometimes I wish Mom would write her version of this story, so I could hear her perspective.)

The second – I remember talking with Mom several years later.

We were sitting in her car while I visited her in Kansas. I feel like it was raining, a sudden thunderstorm. Things weren’t going well with her tennis instructor husband (now a doctor in the Army). She started crying…

“Tell your Dad I’d like to come back,” she said.

But I never said a word to him about it.

Member discussion